Even With High 2022 Inflation, 14-year rate is One of The Lowest in 50 Years

Although Inflation was high in 2022, the average annual rate from 2009 through October 2022, was one of the lowest in the last 50 years.

In 2022, inflation in the U.S. has hit highs not seen in decades, but how bad is it really and what caused it?

If we look at total inflation in the last two decades, it tells a different story. Looking at the average rate of Inflation over this period, it has been at a normal healthy pace over the long run—and that includes the high rates in 2022. The problem is that there was very low inflation for more than 10 years previously, and then we get very high inflation all at once in 2022. When “normal” inflation is spread out over several years, people don’t feel it as much as when it builds up and hits everyone over a one-year period, like in 2022. But overall, prices in 2022 are about where they would be if we had steady inflation little by little over this period. Hard to believe, but that’s what the facts show.

Because of two major events since 2008, inflation has set records of prolonged periods of very low inflation, then, starting in 2021, the country experienced mild inflation, building up to high inflation in 2022. We can show this as we look back, but first: Is inflation good for the economy, and if so, how much inflation is good and how much is bad?

Is Inflation Good or is it All Bad?

Economists generally agree that a little inflation is necessary for a growing and healthy economy, so the government plans for some inflation. The Federal Reserve bank, the nation’s central bank, has set an annual target of 2% inflation, allowing it to periodically go a bit higher—up to around 3%. When it goes above 3% for a month or two and then drops down, there is little concern, but when it keeps climbing, everyone is concerned.

In the first 10 months of 2022, inflation hit a high of 9.1% and a low of 7.5%, with an average of about 8.3%. But if we average the inflation rate over the previous 10 years, going back to 2013, the rate averages out at 2.5% a year. * This is within the parameters that the Federal Reserve considers comfortable for stable economic growth. Part of the problem is that “stable economic growth” rarely happens for long periods. Growth has always come with downturns and upturns. Adding in unrelated crises, like wars and pandemics, which happen periodically, makes for even less predictable outcomes.

If we go back even further, to 2009, the average inflation rate changes even more. At the end of 2008, there was a major economic collapse—often called “The Great Recession.” But its major effect began a few months later in early 2009. When there is a collapse of the economy, demand drops when people lose their jobs and cut back on their buying. Consequently, inflation is low. There was even deflation in 2009 with a -0.4% inflationary average over the entire year. Subsequently, as the economy recovered and demand increased, Inflation slowly went back up until 2020, when the pandemic hit, which had a major economic impact that no one was certain about. Inflation dropped back down to 1.2% and then, in 2021, as the nation recovered from the pandemic, the rate began to rise until it hit the highs in 2022. In other words, the country experienced very low inflation from 2008 through 2020.

The Great Recession, the Pandemic and the Inflation Rate

These two major events, the Great Recession and the pandemic, instigated significant economic changes that caused inflation to fall and then rise again. But the effects from each event were vastly different and we can learn a lot by comparing the two, especially the inflation rates.

The Great Recession was a deep, but normal, recession with unemployment going up, profits dropping and inflation slowing down below the normal healthy inflation rate levels of around 2%. In the first year, 2009, inflation hit a low of -0.4%. The following year (2010) inflation began to rise, but it was still low at 1.6%. In 2011, as the economy began to recover, it hit 3.2%, then in 2012 it was 2.1% as the recovery grew stronger. Then it hit low inflationary rates in the following years of 1.5% (2013), 1.6% (2014), 0.1% (2015), 1.3% (2016), 2.1% (2017), 2.4% (2018), 1.8% (2019). These are typical of previous recession recoveries. The average of the years 2009 through 2019 was very low at 1.6%—below the average of 2% that the central bank sees as healthy. You might call the recovery from the Great Recession a normal “healthy” recovery that was just like other recoveries, except it was from a deeper and more severe recession than any seen since the Depression in the 30s.

The second big event, the pandemic, hit starting in the second quarter of 2020. Average annual inflation that year was at a very low 1.2%. It had not dropped that low since 2015. The pandemic caused a recession, but it was like no recession that anyone had ever seen before, and its effects were unpredictable. There had not been a pandemic in the U.S. in more than 100 years—and never in a modern economy. It was uncharted territory. The economy had just gone through a recovery over the previous eight years and was in a very strong and healthy condition. The pandemic recession was not linked to the normal business cycle, though. Many lost their jobs—even though demand was there—and small and medium-sized businesses closed down, some permanently, some temporarily. Many started working from home, and many just quit working. Unemployment went up. But the government gave out money and extended unemployment benefits to help those in trouble. That put some money into the economy. But the future was still uncertain.

The Pandemic “Recession”

No one was sure what the economy would do or how the government should respond. The economy had never gone through anything like it. In fact, it was hard to call it a recession since people weren’t really being laid off like in a normal recession. Many people were being temporarily laid off “until the pandemic ended.” During the height of the pandemic, many took early retirement and early Social Security benefits. Many started working for themselves and many joined the cash economy, getting unreported income. Crime went up as society was disrupted, plus crime always goes up when people lose their jobs. The poor suffered most, which always happens during rising unemployment. But generally, people had less money and demand was low, which means inflation would be low.

One could say that the pandemic, with layoffs and businesses closing or cutting back, caused a recession. It was like a recession, but it did not have the usual causes. Plus, it had one other unique aspect: It was the fastest recession recovery in history. The pandemic hit the economy in early 2020, then it basically ended in late 2020, and everyone went back to work, and it was basically over by early 2021—all in one year.

As people went back to work, demand increased and inflation went up, hitting 4.7% in 2021. This happened not only in the U.S. but around the world. The pandemic and its associated “recession” caused factories to close or cut back around the world. Before the pandemic, the world’s economy had become more international than ever before. Products were manufactured overseas and then shipped to consumers around the world. When product demand came back, it was difficult for supply lines to come back quickly. The overseas factories and supply lines to bring goods to America, mainly in Asia, grew “organically” and very slowly over several decades going back to the 70s. When demand came back in America, it came back quickly, but these supply lines to overseas factories had to be restarted. It was like rebuilding a car that was taken apart and put in storage.

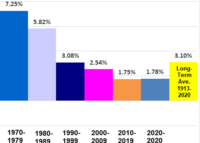

With those two events, the Great Recession and the pandemic, the U.S. had record inflationary lows for many years and then record highs in 2022. But the average from the beginning of 2009 through 2022 was still low at 2.25%, which is as good as it gets for a long-term low inflation rate. If we look at inflation by decade, 2.25% over 14 years is exceptionally low. In the attached graph, inflation in the 2000s was 2.54%, in the 1990s it was at 3.08%, and in the 1980s it was at 5.82%. It’s just that the high inflation mid 2021 through 2022 hit all at once and was not spread out over several years. In other words, the prices in 2022 are pretty much what they would have been if the average inflation rate had increased at a relatively low and steady pace over this period. It just hurts more when it comes all at once.

Low Unemployment and Inflation Rate Average

The state of the economy post pandemic from 2021-2022 was a surprise to most everyone, and the biggest surprise was very low unemployment with two jobs for every person looking for a job. Companies, large and small, were struggling to find enough workers. And demand was booming as the economy’s recovery from the pandemic “recession” went into overdrive.

Economists, who mainly did not predict this situation when the pandemic ended in 2020, started to talk about a recession in 2022, even some saying we were already in one. Then came predictions about a coming recession later in 2022. Then it became 2023, then it was mid-2023, and then it was late 2023. And many predict the worst recession of all time.

What is the main problem with a recession? It’s simple: People lose their jobs. For those who have been saying that we are already in a recession are missing this key ingredient: There’s never been a recession with unemployment this low. Economics is not an exact science and considering the failure of at least 90 percent of economists to predict the Great Recession, I wonder about their opinions today. Maybe they are all trying to make up for not seeing the 2008 crash. But then again, even though economics is not an exact science, these “respected economists” talk like it is. Or maybe they’ve learned their lesson from 2008 and are better economists (I hope so). It reminds me of the old saying: Get five economists together and you get six opinions on where the economy is going. Add an unknown factor like a pandemic and you would probably get 10 opinions.

The other big result of the pandemic “recession” recovery was increase demand, which always causes inflation, or at the least, fears of inflation. In 2021, inflation immediately began to rise in the second quarter of 2021, with an average annual rate of 4.7%. In 2022, inflation increased very quickly. Wages were rising, but not fast enough to keep consumers happy. The “recovery” was going too fast, and with the low inflation for the previous 14 years, inflation was catching up all at once—in one year.

So… what can be done about it?

Rising and Falling Interest Rates’ Effects on the Inflation Rate

The main tool that the government has in controlling inflation is the Federal Funds Rate, which sets the interest rate for borrowing. The Funds Rate is set by the Federal Reserve (the “Fed”), and the one person who has the most power for setting the rate is the chairperson of the Federal Reserve. The theory on controlling inflation: In a strong economy, when demand is high, inflation goes up, therefore increase interest rates to slow down the economy and soften demand. In a weakening economy, when demand is low and inflation too low, lower interest rates to spur the economy and keep inflation rates at a healthy 2%. In a recovering economy, with low inflation, raise interest rates incrementally to stave off inflation. Interest rates that are too low for too long create a situation where there is too much easy money in the economy and inflation will go up. And in the long run, being able to borrow money at a very low cost is not a good thing, so bringing rates up to a “reasonable” level is a good thing.

By the time the Great Recession started in late 2008, the interest rate had dropped steadily from 5.25% in 2007 to around 2% in the third quarter of 2008. The economy started to show signs of weakness in 2007, so the Fed started a regular lowering of the Funds rate to encourage borrowing and investment. By August 2008, it was at 2%. By September, when the crash really came to a head, the rate was dropped to around 1% and by early December it was at .15%. It stayed in that range for the next seven years and the economy continued to recover and grow until the Fed, under Chairwoman Janet Yellen, started to raise the rate in December 2015 when the economy was doing fairly well. Then the rate was slowly but steadily raised over the next three years by Yellen and by the new Fed Chair, Jerome Powell who was appointed by President Trump in early 2018. It reached a low rate of 2.4% by the first quarter of 2019, when Powell indicated the Fed would continue to raise rates. Instead of raising them—and in response to pressure from President Trump—he made no rate change. And then he lowered the rate three times in the third and fourth quarter of 2019, again under pressure from President Trump, even though the economy was continuing to grow. Why the Fed agreed, or succumbed to Trump’s desire, to not only raise rates, but to lower them, was surprising to many, considering that the economy was still doing well. In fact, Fed Chairman Powell later admitted to making a mistake by lowering rates, stating that the economy was in better shape than expected. Lowering the rates was a big mistake, the effects of which would be felt much later.

In late 2019 and early 2020, inflation was below the 2% target. This was before the pandemic caused economic problems. Raising rates would have been the correct thing to do to keep the economy from overheating and causing rising inflation. Instead, only a few months later in the spring of 2020 when the effects of the pandemic took hold, demand fell, and inflation stayed very low the rest of the year. If, instead of lowering rates in 2019, the Fed had continued to raise them, or even just stabilize it, inflation would have been kept in check when the pandemic ended just months later in late 2020 and everyone went back to work. Instead, inflation started to rise in March 2021 and continued a steady increase until it started to increase very quickly in the second quarter of 2021 (going over 5%). This was another time to raise rates incrementally, but that didn’t happen. As it continued into 2022, the Fed woke up and finally started to raise rates monthly to stave off the extreme inflation through 2022. It was too late to ease the pain of low but steady inflation.

But the average annual inflation from 2009 through 2022 was, as noted above, only 2.25%—a very healthy rate over the long run. Rates should never have been lowered in 2019. The Fed should have continued to raise them instead, which is what they were doing in the years leading up to 2019. These were not big jumps, but incrementally small ones of only around .5% a year on average. The rates should have been left alone at around 1.5% in early 2020. Lowering the rate to less than 1% resulted in very low inflation in 2019-2020 and very high inflation in 2021 and 2022. The Fed didn’t follow its own historical guidelines of raising rates in good times to control future inflation.

Consequently, 2022 hit consumers all at once instead of slowly over the years. Again, at only 2.25% average per year, prices in late 2022 are about the same as they would have been anyway. But no one thinks of it like that. Why? Because Trump and Powell are to blame for lowering the rate in 2019, and Biden and Powell are to blame for not raising them in 2021, although that was too late to make a major impact right away. One thing about inflation: it takes time for changes in the Fed rate to affect a massive economy like the U.S., meaning many months to years. Politically speaking, everyone is looking for someone to blame, but no one wants to take the blame.

The Perfect Storm of Inflation

In conclusion, it was good that the economy had low borrowing rates during the pandemic, which was at its worst from the spring of 2020 until late that year. There was no reason to raise them; businesses weren’t borrowing during that time anyway. They were saving money, as were consumers, who experienced record savings rates, which was later money spent in 2021-2022, which helped fuel inflation. But it would have been best to not lower the rate in early 2020, when it was lowered substantially. It was down to 0.5% by April from 1.5% only 4 months earlier. Rates should probably not have been raised during that period but should have been in 2019. They should have at least stabilized the rates in 2020, not lowered them.

High inflation in 2022 was caused by the pandemic more than any single factor, and the pandemic was an event never experienced in over a century—and not at all in the modern world of an international economy. The country, and the world, will continue to feel the effects of the pandemic for years to come, so beware of those who are so certain in their predictions of total collapse in the coming year. Anything could happen, including total economic expansion and prosperity, short-term recession, long-term recession—or even another pandemic. After all, we are in uncharted territory. At the pace the world is changing—even without the pandemic—we will stay in uncharted territory for a very long time, perhaps forever, because it is the incredibly fast pace of technological improvements that is the main driving factor in the modern world—and the slow pace of human evolution that is trying to deal with it that will determine our future. That clash makes the future exceedingly difficult to predict, and a pandemic makes that even more difficult.

The pandemic might have been the most important single factor in the rise in inflation, but it wasn’t the only factor. There were three factors that created the perfect storm of inflation in 2021-2022: First was not continuing to raise rates in 2019, but instead lowering them and doing so again in early 2020. These decisions were not economic decisions, but political decisions. Second was the pandemic. And third was not incrementally raising them again starting in late 2020 and on into 2021, although it might have been too late, anyway. But it couldn’t have hurt the situation. Instead, the rates had to catch up with the economy all at once in 2022. The perfect storm. And no one saw it coming.

Inflation will slow down on its own, mainly because it has caught up with itself.

*******

* Many people don’t understand the monthly inflation reports. It’s important to know that when the inflation rate is 5% one month and then 6% the next month, that doesn’t mean that prices went up 5% the first month and then they rose 6% higher the next month. It means that in the first month, prices were 5% higher than the same month of the previous year, and the following month the prices were 6% higher than the same month the previous year. Over 12 months, the average is taken and that is the annual rate of how much inflation there was over the previous year.